The My Climate Risk (MCR) Education Working Group conducted two webinars on "Climate and Colonialism" earlier this month. Here is a detailed highlight of the discussions.

Image: Wikipedia

My Climate Risk, Education Working group

October 5-6, 2023

Anne-Lise Hadzopoulos

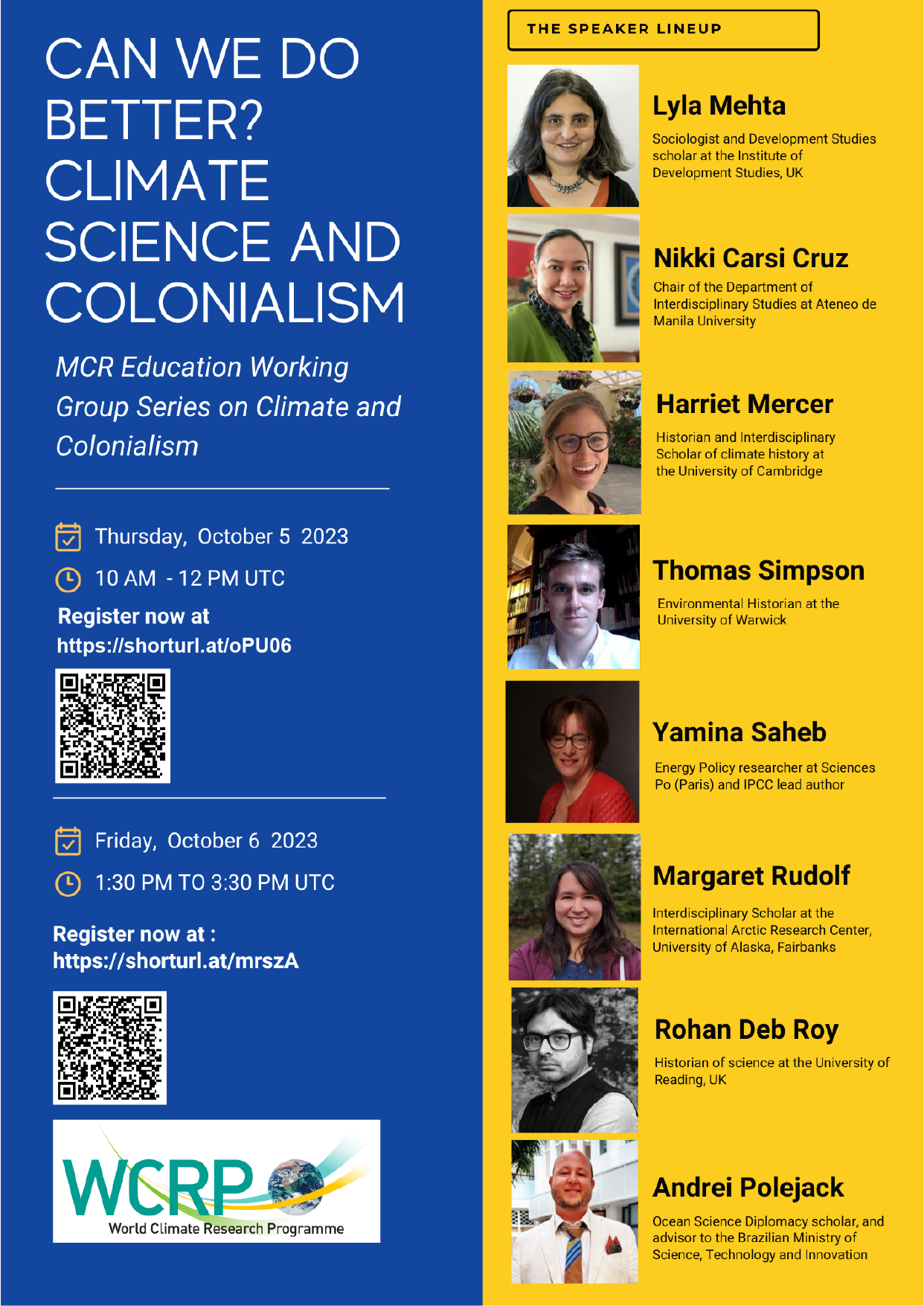

My Climate Risk's Education Working Group organized a 2-day webinar on Climate and Colonialism on October 5 and 6, 2023. The sessions posed the essential question 'can we do better'? During both days, participants gave a reflection on the different ways today's climate science and environmental policies perpetuate colonial bias. The speakers deconstructed the entanglement between sustainability and colonialism as well as the way forward. Speakers gave solutions to reverse the trend and include the most affected and vulnerable communities to climate change in mitigation and adaptation.

Dr. Regina Rodriguez, co-chair of My Climate Risk, kicked off the two-day webinar by highlighting the interconnectedness of models, observations, and process understanding within the context of uncertainty. She envisions the development of a revolutionary bottom-up climate information framework rooted in regional climate knowledge. Inspired by the economic theory of development encapsulated in "Schumacher's 'Economics as if People Mattered'," Regina, along with Theodore Shepherd, co-authored the article "Small is Beautiful: Climate-Change Science as if People Mattered." Their work addressed a vital research question: What are the challenges of integrating regional expertise into climate science? Their conclusion offered three pivotal recommendations: understanding the complexity of regional contexts, simplifying science and confronting uncertainty, and empowering local communities. To bring these recommendations to fruition, My Climate Risk established networks hubs across the globe, working towards the transition to a more open and inclusive approach to climate science that aligns with the Global South.

Before the first panel started, Dr Vandana Singh, Lead of the MCR Education Working group, elaborated on the intersection of climate science and colonialism. She stated that colonialism has had on how communities experience climate change, but it's also influenced how we perceive science. Science is often seen as objective, but colonialism has painted Western culture as the sole source of scientific knowledge, creating global power imbalances. These disparities in the scientific community and the colonial legacy must be acknowledged if we want to make climate information relevant and actionable for local communities. Conventional education has not adequately addressed this issue.

During this webinar, our speakers explored the entanglement of climate science and colonialism and discussed how we can create a more equitable and responsive approach to climate education and research. The panel was moderated by Dr Kendra Gotangco Gonzales from the Philippines Manilla Hub.

Addressing (post)-colonial and Western biases in climate science: examples from South Asia by Dr Lyla Mehta, Sociologist and Development Studies scholar at the Institute of Development Studies, UK

The definition of sustainability is at the root of the entanglement between sustainability and colonialism. The term 'sustainability' was coined in the 18th century by a German forester to define long-term forest management in a framework geared towards economic profit. This definition of sustainable development was at the heart of colonial land management policies which resulted in natural resource extraction accompanied by racialized discriminatory labor practices perpetuated to this day. Colonial legacy in India has constructed certain landscapes with extreme events as marginal and needing landscape management such as irrigation systems to normalize them.

Today, colonial biases in environmental policy can be perpetuated with policies that dispossess local communities from their land in the name of producing renewable energies or label traditional uses of land as a threat to conservation. Lyla Mehta illustrated cases where indigenous practices are seen negatively because of colonial biases with misconceptions about the impact of the communities' pastoral way of life from Kutch. Indeed, the herders from Kutch's cultural identity and day-to-day are deeply tied to their pastoral activities involving the Kharai swimming camels. Over the past years, the scientific community has blamed pastors for any negative changes in the Kutch area mangroves. This led Professor Mehta along with a group of researchers from the Tapestry project to conduct a study integrating GSI mapping methods and indigenous knowledge to monitor the impact of camel browsing on the mangroves. This soon-to-be-published research proves that there are no negative impacts of camel pastoring in the mangroves. On the contrary, pastoral activities are compatible with thriving ecosystems as believed by the Kharai community. This study proves to be groundbreaking as it could change the negative biases towards Kharai pastoring in the scientific community and contribute to validating the lifestyle of the community.

Nagbabago and Ihip ng Hangin (The Wind Change Direction): Colonialism and Climate by Dr Nikki Carsi Cruz, Chair of the Department of Interdisciplinary Studies at Ateneo de Manila University

Inspired by Galtung's triangle of violence, Nikki deconstructed the parallels between the three types of violence and the environmental colonial legacy. She illustrated her point with metaphors about the manifestation of direct violence through physical acts such as the slashing of the forest, structural violence by processes such as pollution and cultural violence with buzzwords such as 'economic sustainable growth'. When growth represents the commercialization of nature, development becomes equal to transforming nature into industrial activity which is in itself unsustainable. It also represents cultural violence because commercialization destroys the holy and sacred bond of local communities with nature. In the Philippines, this bond persists through distinct practices of Christianism inherited from the pre-colonial area. Today, the way forward is to decolonize environmentalism by deconstructing internalized binaries. It is essential to radically change attitudes rather than perpetuate a business-friendly environmentalism. Nikki ended her speech by highlighting the Pope's new book, 'laudato si', which she read as an atonement from the church and as a bridge between indigenous and Western cultures.

How to do better with histories of climate science by Dr Harriet Mercer, Historian and Interdisciplinary Scholar of climate history at the University of Cambridge and Dr Thomas Simpson - Environmental Historian at the University of Warwick

Tom Simpson and Harriet Mercer introduced their research on the often-overlooked histories of the intersection between climate science and colonialism. Tom began by shedding light on the historical roots of climate science, tracing its origins to the 19th and 20th centuries—a time when most of the world was under colonial rule. Remarkably, climate science was already being practiced within local communities, which observed changes in their environment. During the colonial era, settlers in these new lands leaned heavily on the knowledge of these local communities to construct the foundations of modern climate science. Tom illustrated this point with the example of Mihr Izzet Ullah's 1812 quote regarding the evolution of the Himalayan Glacier. Ullah’s quote was later translated and published multiple times by Horace Wilson, an esteemed colonial scientist, to the extent that Wilson was attributed with his analysis of glaciers.

Harriet drew attention to the present-day recognition by the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) of the role of colonialism in climate change's impact on vulnerable communities by working group II. However, this acknowledgment was conspicuously absent from the IPCC's Working group I report on climate science. This research gap prompted Tom and Harriet to explore the nexus of colonialism and climate science, culminating in their publication in Wires Climate Change journals. Their research brought to light several key themes:

- The historical overlooking of indigenous knowledge by colonial scientists who failed to credit them for their contributions.

- The devaluation of indigenous knowledge, with colonial scientists often labelling their failures as data collection errors from their local informants.

- The shaping of climate science by ideological measures aligned with the goals of extractivism and control over the colonized.

- The historical concentration of climate monitoring stations in the Global North.

Harriet concluded with the importance of shifting the paradigm and deconstructing colonialism in climate science. Focusing solely on the impact of colonialism on marginalized communities portrays the colonized communities as passive actors rather than active producers of knowledge. This revelation underscores the need to reevaluate the dynamics of knowledge production and distribution within the realm of climate science.

Q&A Highlight

The Q&A session of the thought-provoking event "Climate and Colonialism: Can We Do Better?" brought forth illuminating insights and perspectives on the complex interplay between climate adaptation and colonial patterns. Here are the key highlights:

1. Reproducing Colonial Patterns in Adaptive Measures

Lyla addressed the question of how adaptive measures can inadvertently perpetuate colonial patterns. She emphasized the importance of solutions that are locally owned and appropriate. Often, this is not the case, leading to the potential reproduction of neocolonial patterns. The need for context-specific approaches was a critical point of discussion.

2. Rethinking Notions of Progress

Nikki challenged conventional notions of progress and development. She urged us to reconsider our dreams of development and progress, highlighting that there is no linear definition of progress. With planetary boundaries broken, Nikki called for a shift in our perspective. The pandemic served as a wake-up call, prompting a reevaluation of past values and the recognition of our lost connection to self-reliance. Nikki emphasized the need for change, even if some scientific narratives support the continuation of problematic practices.

3. Empowering Indigenous Practices and Rethinking Science Domains

The discussion also touched on the importance of empowering and supporting indigenous practices that have long been marginalized. There was a call to rethink how we approach science-based domains like ecology. Lyla noted that it is not the role of outsiders to "empower" indigenous practices. Instead, she emphasized the value of learning together and taking collective action. Scientists can play a vital role by validating indigenous knowledge and lifting it up without introducing co-optation.

Dr Vandana Singh ended the session by making a summary of the key points touched upon by the panellists and closing remarks.

On the second day, scientific studies and projects were evaluated under a anti-colonial lens to detangle colonial legacies in the scientific realm. Dr Amadou Thierno Gaye, from the Senegal MCR hub, introduced the session by highlighting the MCR's goal to develop a new science that decolonizes knowledge production. Vandana Singh expanded on the notion of the necessity for decolonization as colonialism has taken new forms, structures of development and knowledge over the years. This panel was moderated by Ana Duran, Nadia Testani and Vandana Singh.

Coloniality of the so-called 'Paris Compatible' climate mitigation scenarios by Dr Yamina Saheb, Energy Policy researcher at Sciences Po (Paris) and IPCC lead author

During her talk, Yamina Saheb demonstrated how coloniality affects Paris Agreement climate targets and IPCC report models giving an unfair advantage to the Global north while condemning the Global South to poverty cycles in the name of 'sustainable development growth'.

Yamina first showed how IPCC's models underestimate the greenhouse gas (GhG) emissions emitted by the Global North by only taking into account total present-day emissions by region. This calculation method shows a shift in the regions that emit the most GhG emissions going from the United States and Europe in the 1990s to East Asia in the last decades. These models, conveniently, ignore the fact that developed countries from the Global North have reduced their emissions by deferring them and outsourcing the production of goods they import. Additionally, if we examine GhG emissions per capita, the Global North emits more than Global South countries. If cumulative emissions were counted, models would show that the Global North has emitted the majority of GhG over human history. The consequences of these miscalculations amount to the underestimation of the Global North's impact on climate in international climate mitigation policies such as the Paris Agreement which aims for carbon neutrality by 2050 as a target. However, if the previous facts were considered in climate models, the Global North would need to become climate neutral by 2030. There are structural barriers that impede changing the models used by the IPCC as all the models need to comply with Paris Agreement targets. Moreover, IPCC climate models are produced by scientists from the Global North.

Yamina dedicated her research to evaluating the consequences of underestimating the emissions of the Global North for the economic development of the Global South. She created models to evaluate how the current Sustainable Development Pathway coupled with current climate targets will affect the evolution of final energy per capita, emissions per capita, energy and carbon intensity for developing countries. Research findings showed that based on current climate targets, developing countries' final energy and emissions per capita will remain low which means their access to modern amenities will remain scarce. Additionally, energy and carbon intensity will remain high in developing countries which points to lack of progress in energy efficiency.

In conclusion, if the Global North keeps understating their impact on climate, the Global South won't have a chance to industrialize and grow economically. The way current climate models are calculated, and climate targets are shaped represents a 'colonization of the atmosphere'.

Co-Production of Knowledge: Colonialism within Arctic Research by Dr Margaret Rudolf, Interdisciplinary Scholar at the International Arctic Research Center, University of Alaska, Fairbanks

In her presentation, Margaret shared her family's experience as a member of the native Iñupiaq community from King Island, Alaska. She explained how members of the Iñupiaq community including her mother's family had to relocate to a larger city due to lack of teachers and governmental policy which made education compulsory. This forced displacement led to cultural alienation and language loss. In the education sector, indigenous knowledge has been dismissed and co-opted by settlers. Consequently, over her career, Margaret has grappled with the binary perception of being considered either "Indigenous" or "Scientist".

These factors are important to acknowledge while considering knowledge production in the scientific realm and indigenous knowledge. In an effort to lead transformative change, Margaret focused her research on Co-production of Knowledge and developed a model for incorporating indigenous methodologies and pre-colonial research as well as triple-Loop Learning. Her work contributes to filling gaps in the transmissions of indigenous knowledge in climate, an area where progress is needed.

However, there are cognitive barriers to change since mainstream institutions tend to engage in co-optation of knowledge rather than co-production. Margaret illustrated such issues with the example of the Navigating the New Arctic (NNA) program implemented by the NSF. Aimed at capacity building for Arctic people in climate science, the NNA programs were designed by outsiders, who positioned themselves as trainers and saviors rather than equals. Two letters from leaders of Alaska's indigenous communities were written to the NSF to highlight the problematic dimensions of the project which failed to enact co-production of knowledge.

A Historic Perspective on Colonial Legacy of Scientific Experiments by Dr Rohan Deb Roy, Historian of science at the University of Reading, UK

Rohan Deb Roy delved deep into the colonial legacy of scientific experiments, shedding light on a dark chapter in history that continues to reverberate today. The core of Rohan's presentation centered on his study, on decolonizing mosquitoes: "Ronald Ross and the problem of invisible labour, British India, c.1900" He posed a fundamental question: Are there colonial patterns in medical anthropology? This study served as a powerful illustration of the deep-rooted colonialism in scientific endeavors.

One striking example came from the history of British scientist Sir Ronald Ross, who won the Nobel Prize for proving that mosquitoes caused Malaria in 1902. Rohan revealed that Indians played an indispensable role in Mr. Ross's experiments. Indian individuals were subjected to being bitten by infected mosquitoes and other forms of experimentation, all in the name of scientific progress. Rohan also shed light on the case of an Indian associate, Bux Mahomed, who, despite his critical role, remained uncredited and was merely described as an assistant when he was, in fact, a surgeon. Mr. Ross even confessed to forgetting the names of his Indian "assistants," illustrating the erasure of their contributions.

The use of Indian bodies as human subjects in these experiments underscored the extent to which colonial powers prioritized scientific discoveries at the expense of the well-being of colonized individuals. Rohan challenged the audience to contemplate whether such practices continue to persist today. He concluded on a hopeful note, emphasizing the importance of more critical engagement with these issues in the present and future.

Coloniality in Science Diplomacy - Evidence from the Atlantic Ocean by Dr Andrei Polejack, Ocean Science Diplomacy scholar and advisor to the Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation

Andrei Polejack engaged with the complexities of coloniality in science diplomacy, highlighting on the enduring legacy of colonialism in our modern world. He began by drawing a distinction between colonialism and coloniality, emphasizing that while colonialism formally ended with the independence of colonies, coloniality's legacy endures. He underscored this point by referencing historical events such as the division of territories between Portugal and Spain in 1494 and the treaty of Zaragoza in 1529, which shaped the course of colonialism. He then delved into the dark history of the slave trade, highlighting the inhumane treatment of humans as commodities. Andrei made it clear that colonialism didn't truly end when colonies gained independence. Healso explored the role of science in colonial rule, explaining how it was used to identify and classify people, serving as a tool for the colonial crown.

Moving to contemporary issues, in his recent research, Andrei discusses the influence of coloniality on today's oceanography through factors such as 'science diplomacy' and 'parachute science’. The speaker explained that science diplomacy involves the political use of science to categorize countries based on their technical capabilities, often reinforcing inequalities. According to his research, South American ocean scientists are amongst the least published and cited for their work. The prevalence of "parachute science" where researchers from the Global North conduct research in the Global South without leaving behind the necessary capacity and knowledge is impeding any form of progress can account for this disparity. Andrei challenged the prevailing paradigm of "Leave No One Behind," highlighting disparities in the distribution of ocean scientists globally, with a concentration in the Global North. Indeed, the concentration of knowledge production in the Global North and underrepresentation of South American scientists are problematic as science can also serve as a form of soft power shaping international affairs.

Q&A Highlight

The Q&A segment during the thought-provoking event "Climate and Colonialism: Can We Do Better?" provided valuable insights and perspectives on the intricate relationship between climate adaptation and colonial influences. Here are the key takeaways:

1. The way forward for IPCC:

Yamina emphasized the importance of increased collaboration among researchers from the Global South to expose colonial elements within IPCC climate scenarios.

2. Exploitation of anti-colonialism by Right-Wing Groups

Dr Rohan discussed how right-wing factions in the Global South are attempting to exploit decoloniality for their own purposes.

3. Paths to Overcoming Colonial Challenges:

Andrei highlighted the necessity of seeking pathways to transcend our colonialist predicament, drawing inspiration from Frantz Fanon.

Dr. Paola Andrea Arias Gomez concluded the session with closing remarks and a summary.

Bartlett, Cheryl, Murdena Marshall, and Albert Marshall. “Two-Eyed Seeing and Other Lessons Learned within a Co-Learning Journey of Bringing Together Indigenous and Mainstream Knowledges and Ways of Knowing.” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 2, no. 4 (November 1, 2012): 331–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-012-0086-8.

Chimakonam, Jonathan O. Ezumezu: A System of Logic for African Philosophy and Studies. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11075-8.

Enloe, Cynthia H. Bananas, Beaches and Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics. Second edition, Completely Revised and Updated. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2014.

Grove, Richard. Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600-1860. Studies in Environment and History. Cambridge (Mass.): Cambridge university press, 1996.

Kavach, Margaret. Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations and Contexts, 2009.

Kawerak, Danielle. “Knowledge Sovereignty and the Indigenization of Knowledge,” 2020. https://kawerak.org/knowledge-sovereignty-and-the-indigenization-of-knowledge-2/.

Kerkvliet, Benedict J. “Pasyon and Revolution: Popular Movements in the Philippines, 1840–1910. By Reynaldo Clemena Ileto. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1979. 344 Pp. $19.75 (Cloth); $13.75 (Paper). (Distributed by The Cellar Book Shop, Detroit, Mich.).” The Journal of Asian Studies 41, no. 2 (1982): 414–15. https://doi.org/10.2307/2055014.

Littlewood, Roland. “Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks – Reflection.” British Journal of Psychiatry 203, no. 3 (2013): 187–187. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.113.127324.

Mehta, Lyla, Hans Nicolai Adam, and Shilpi Srivastava, eds. The Politics of Climate Change and Uncertainty in India. Pathways to Sustainability. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 2022.

Mehta, Lyla, Shilpi Srivastava, Synne Movik, Hans Nicolai Adam, Rohan D’Souza, Devanathan Parthasarathy, Lars Otto Naess, and Nobuhito Ohte. “Transformation as Praxis: Responding to Climate Change Uncertainties in Marginal Environments in South Asia.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 49 (2021): 110–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2021.04.002.

Mercer, Harriet, and Thomas Simpson. “Imperialism, Colonialism, and Climate Change Science.” WIREs Climate Change, June 21, 2023, e851. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.851.

Pedersen, C., M. Otokiak, I. Koonoo, J. Milton, E. Maktar, A. Anaviapik, M. Milton, et al. “ScIQ: An Invitation and Recommendations to Combine Science and Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit for Meaningful Engagement of Inuit Communities in Research.” Arctic Science 6, no. 3 (September 1, 2020): 326–39. https://doi.org/10.1139/as-2020-0015.

Polejack, Andrei. “Coloniality in Science Diplomacy—Evidence from the Atlantic Ocean.” Science and Public Policy 50, no. 4 (September 14, 2023): 759–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scad027.

Rodrigues, Regina R, and Theodore G Shepherd. “Small Is Beautiful: Climate-Change Science as If People Mattered.” Edited by Efi Foufoula-Georgiou. PNAS Nexus 1, no. 1 (March 2, 2022): pgac009. https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgac009.

Roy, Rohan Deb. “Science Still Bears the Fingerprints of Colonialism.” Smithsonian Magazine, 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/science-bears-fingerprints-colonialism-180968709/.

Srivastava, Shilpi, and Lyla Mehta. “Uncertainty in Modelling Climate Change: The Possibilities of Co-Production through Knowledge Pluralism 1.” In The Politics of Uncertainty. Routledge, 2020.

TAPESTRY. “Why Sustainability Sciences Must Be Decolonised.” TAPESTRY (blog), April 25, 2022. https://tapestry-project.org/2022/04/25/why-sustainability-sciences-must-be-decolonised/.

Wilson, Shawn. Research Is Ceremony, 2008.

Yua, Ellam, Julie Raymond-Yakoubian, Raychelle Daniel, and Carolina Behe. “A Framework for Co-Production of Knowledge in the Context of Arctic Research.” Ecology and Society 27, no. 1 (March 26, 2022). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12960-270134.